Another user in Kenya, Peter Kariuk, wrote: “We need a united Africa that will not be a slave to #BlackChina”.

However, China’s official response has stopped admitting that discrimination has occurred or apologizing for it.

The Global Times, a nationalist tabloid controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, went a step further, publishing an article entitled: “Who is behind the fake news of” discrimination “against Africans in China?”

Traditionally, Beijing has described racism as a Western problem. But for many Africans, whose countries have been strongly intertwined economically with Beijing in recent years, the Guangzhou episode highlighted the gap between the official diplomatic warmth that Beijing offers to African nations and the suspicion that many Chinese have for Africans themselves.

And this has been a problem for decades.

No racism in China

The West really began to notice – and criticize – China’s relations with Africa in 2006, following a landmark summit that saw almost all African heads of state descend to Beijing.

However, China’s ties with Africa date back to the 1950s, when Beijing befriended the new independent states to position itself as a leader in the developing world and to counter the power of the United States and the USSR during the cold war era.

The presence of African students in China was very unusual.

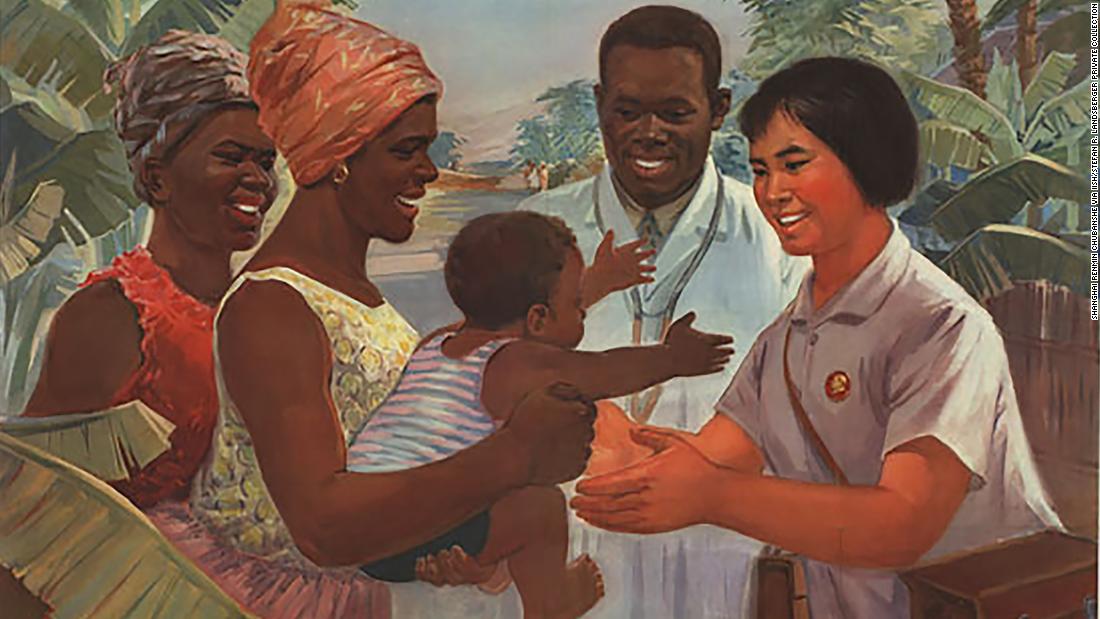

Most foreigners fled China after the Communist Party came to power in 1949. When African students began arriving in significant numbers in the late 1970s, China was just beginning to open up to the world. The vast majority of people still lived in rural areas without access to international media and hadn’t seen a black person outside of the propaganda posters – not to mention meeting one.

From the outset, clashes have been reported across the nation.

“The Chinese have deceived us,” Liberia told Solomon A. Tardey. ” Now we know the truth. We will tell our governments what the truth is. ”

A race riot in China

By 1988, a total of 1,500 of the 6,000 foreign students in China were African and had been dispersed on campuses across the country – a tactic designed to dilute racial tensions, according to a 1994 report by Michael J Sullivan in China Quarterly magazine.

But the attempt did not work and anti-black tensions broke out on the eve of Christmas that year in the eastern city of Nanjing, causing a crowd of Chinese protesters who chased Africans out of town.

Africans claimed that when they tried to bring a Chinese friend into dance, they were insulted with “black devil” calls and a fight ensued, according to Sullivan.

Whatever the real count, what happened next has been well documented.

Later that night, some 1,000 local students surrounded the African dormitory after rumors swept the campus that they were holding a Chinese woman against her will. Chinese students threw bricks through the windows.

After the police broke the scene on Christmas day, some 70 African students decided to flee the campus and walked to the city train station, hoping to travel to Beijing where they had embassies. Other dark-skinned foreigners, including Americans, also fled, fearing for their safety.

On campus, word spread that the Chinese hostage was dead.

As the crowd approached, the police cleared all black Sthey went to a nearby guesthouse, where they were held until several Ghanaian and Gambian students were arrested for fighting campus dance.

The other Africans were accompanied by bus to campus – and warned against going out at night.

Kaiser Kuo, Chinese-born guitarist of American origin in the Tang Dynasty rock band, and founder of the multimedia group Sup China, was studying at the Beijing University of Language and Culture that Christmas, living in a dormitory with students from Zambia and Liberia. Remember to hear about the riots in the race.

“They were angry at the Africans that apparently the honor of a Chinese woman had been insulted,” he said. “This is one of the things where the voice kept swelling. When it reached my ears, the version was that a Chinese girl had been raped to death, when of course there was no evidence of anything like it.

“As far as I know, it was more like an African man had asked a Chinese girl.”

Anti-African protests

The Nanjing event was not an anomalous one. In the city of Hangzhou, students claimed that Africans were carriers of the AID virus in 1988, although foreign students had to test HIV before entering the country, Barry Sautman wrote in China Quarterly.

Then, in January 1989, around 2,000 Beijing students boycotted the classes to protest Africans who attended Chinese women – a recurring lightning rod issue. To Wuhan that year, posters appeared on campuses calling Africans “black devils” and urging them to go home.

Kuo recalls: “You know, around me, there was this real concern among African students about this type of xenophobia on the rise on college campuses.”

This created a problem for Beijing, Sautman wrote, as it undermined China’s credentials as a leader in the developing world – and hostilities did not go unnoticed at home.

Just as African media across the continent were outraged by the Guangzhou incident in April 2020, newspapers in Africa reacted indignantly in the 1980s. A Kenyan publication claims that they were not “accidental”, wrote Sautman. A Liberian newspaper spoke of “yellow discrimination”. A Nigerian radio station claimed that Chinese students “could not bear to see Africans” mingling with Chinese girls.

The Chinese ambassador to the Organization of African Unity (OUA), the predecessor of the African Union, was called to answer for what was happening in China, and the OAU secretary general called him “incognito apartheid”.

As a result, many African students have left China. During the same period, China announced a reduction in interest-free loans for Africa, marking a cooling off of official relations, although ties have never been broken.

Now a professor of social sciences at the University of Science and Technology in Hong Kong, Sautman says that while anti-African protests in the late 1980s were about race, they were also a way for Chinese students to express broader sentiment. anti-government.

“The people who attended anti-African demonstrations back then were college students and those students were somehow jealous of African students,” he says.

“They saw them live better than they did because they got subsidies from their government and the Chinese government, and they also thought that Africans acted more freely than Chinese students,” says Sautman.

Is Chinese racism the same as Western racism?

As China’s interaction with Africans increased in the 21st century, the embarrassing divide between Beijing’s public friendship extends and private suspicion of citizens has once again sparked moments of racial tension.

“Much of China’s sober intolerance is based on color. It is no exaggeration to say that many of my countrymen have a subconscious flattery of races more than we do,” he said.

“(It seems) a definitive racism, but on closer inspection it is not totally based on race. Many of us even look towards Chinese companions who have darker skin, especially women. The beauty products they claim to whiten the skin always gets a prize. children are constantly praised for having fair skin “.

But more recent events have undermined the idea that discrimination against blacks in China is not racism.

The following year, a museum in Wuhan city apologized for the presentation of an exhibition that contrasted images of African peoples and African wild animals creating similar facial expressions. So in 2018, the annual gala for the national CCTV station broke loose after a Chinese woman appeared in a black face.

“There is a classic discussion about whether Chinese racism is racist in the way it is imagined in the West or Europe, or it is a different kind of discriminatory policy,” says Winslow Robertson, founder of Cowries and Rice, a society of China-Africa management consultancy.

“My feeling is that it’s racism. Is it identical to what we see in the United States coming out of the slavery of castles? No. But if you define racism as based on something that you can’t change about yourself, then yes it’s racism. “

Discrimination against Africans in China during the coronavirus pandemic, he adds, highlighted this fact.

But Paul Mensah, a Ghanaian trader who has lived for five years in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, says that the treatment of Africans in China during the Covid-19 pandemic has shaped his perceptions of racial attitudes in the country.

“I thought racism was inherent in America, but I never thought that people in China would do this,” says Mensah. “Before when (the Chinese) saw a black person, they touched your skin and your hair, and I thought it was out of curiosity because many of them don’t travel. But this is racism and there is no punishment for it.”

Sautman, who wrote the document on the Nanjing uprising, says that if China is serious about eliminating the mistreatment of foreigners, it should punish those who report abuse and racial discrimination.

Article 4 of the Chinese constitution states that “all ethnic groups in the People’s Republic of China are equal … discrimination and oppression of any ethnic group is prohibited. It is forbidden to undermine ethnic unity and create ethnic divisions”.

Without a forced legal deterrent, Sautman says it will be difficult to change the way Chinese treat Africans. “There is no place in the world where racial discrimination has been reduced without taking such actions,” he says.

Coffee enthusiast. Travel scholar. Infuriatingly humble zombie fanatic. Thinker. Professional twitter evangelist.